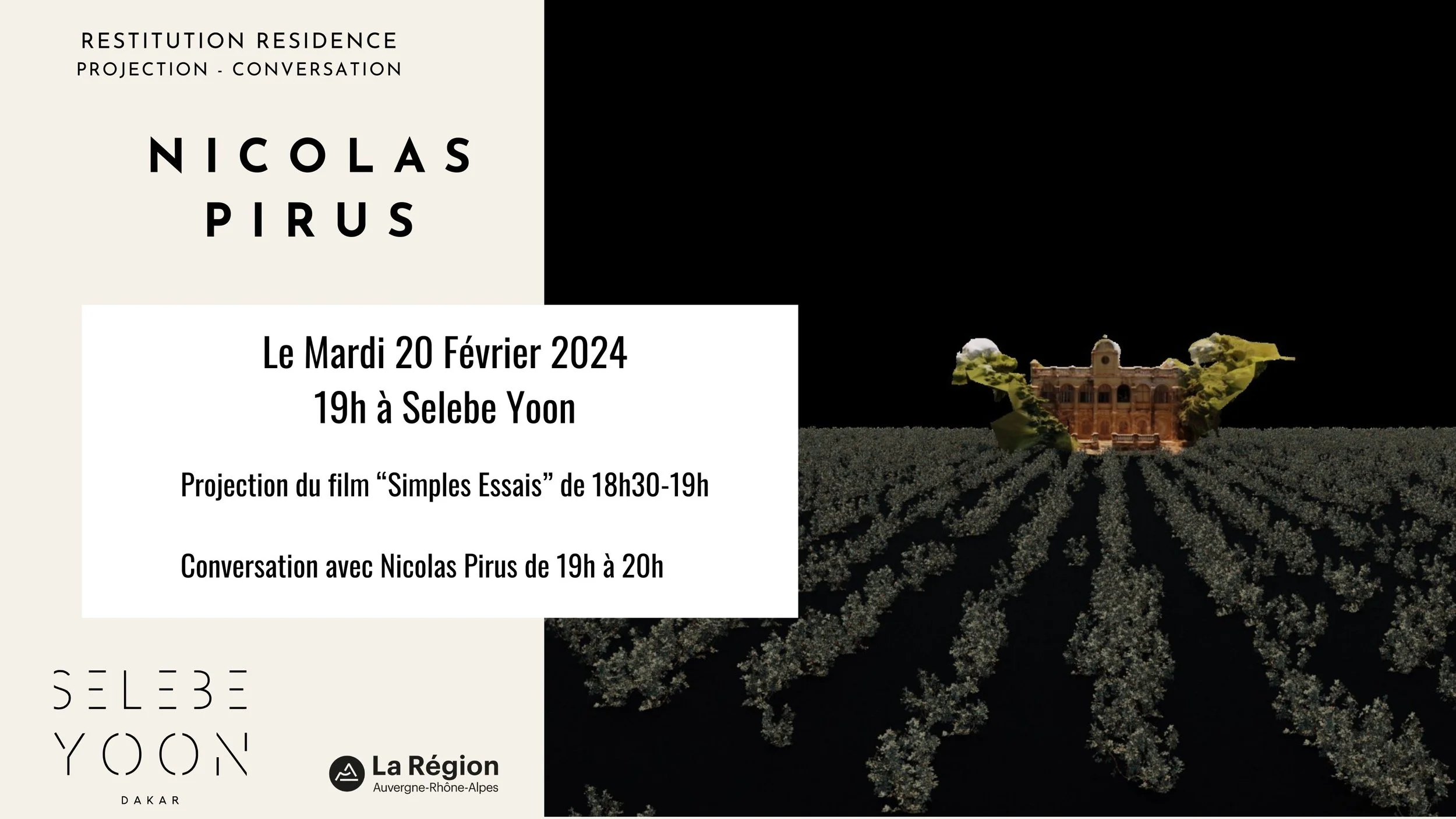

Screening and Conversation with Nicolas Pirus

Residency Restitution: Nicolas Pirus in conversation with Jennifer Houdrouge

Event date: February 20th, 2024, 7PM at Selebe Yoon

Film still of Nicolas Pirus film Simples essais, depicting a 3D model of one of the plants he discovered in the archives during his research.

Nicolas Pirus is a French artist who lives and works in Saint-Etienne. He graduated from the Beaux-Arts de Bourges and the École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. His work combines film, animation, 3D, writing and installation. He is particularly interested in forgotten narratives and the possible or impossible forms of a digital ecology, with care at the heart of the new narratives he proposes. This is why he works in places where it is possible to bring intimate or collective voices that try to respond to presents in crisis, particularly on the theme of environmental or pharmaceutical issues. His cinema proposes a space between the real, the virtual and the imaginary, which become places of welcome that invoke rather than represent or summon.

Jennifer Houdrouge: During your residency at Selebe Yoon, you worked on the link between botany and colonialism in Senegal. Can you tell us about the context and your research topic?

Nicolas Pirus: The link between botany and colonialism emerged gradually in my practice. I've always been interested in botany - plants, greenhouses, gardens and herbariums have always fascinated me. During my research, I asked myself how all these elements were constructed, and above all why. Little by little, by looking at the history of objects and places, I came to determine a link between botany and colonialism. It's a fairly strong link historically, since the establishment of botany is linked to colonialism, to the great voyages, and is nourished by all the colonial missions that brought together researchers and botanists in support of the Compagnie des Indes, or exploration missions to collect a body of knowledge about plants in order to index and archive it, to build up a matrix that would serve as a reservoir of information for planning colonial policies.

JH: From a historical point of view, what methods were used during these colonial missions? For example, in your first film you talk about Michel Adanson, so how many centuries have you gone back in history?

NP: Michel Adanson is indeed from the 18th century - he arrived in Senegal in 1748. His arrival marked the beginning of the history of French botanical missions in Senegal. Adanson was the first French botanist to come and index plants using Western scientific classification methods. What I find particularly interesting is the reason why he came to Senegal - he went first and foremost out of personal ambition, wishing to make a name for himself in the history of botany, as the Senegalese climate had demotivated a large number of naturalists. At the time of his departure, he was working in the King's garden. Louis XV supported the ambition of the voyage but did not finance it - Adanson left at his own expense, then managed to obtain a modest post with the Compagnie des Indes, involved in the trade in plants and colonial crops.

JH: Talking about your first film, you said that it enabled you to unravel the issues around colonial botanical missions that you wanted to explore. What issues would you like to explore in your next film?

NP: Yes, it was my first research film where I started to unravel and break down this story in order to understand it - in particular the story of Michel Adanson. What's more, a large number of the herbariums collected and compiled during these missions are now available online in digitised form from a fairly large number of natural history museums. The free access given by these institutions to their collections amassed during colonisation has the potential to shed light on the implications of the colonial missions - I didn't know if I was going to be able to study them. There are, of course, many implications caused by free access to these old documents, because of course you uncover very problematic parts of the story. I was also interested in the history of the Taïba phosphates in Senegal. In the archives at IFAN (Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire/Musée Théodore-Monod d'art africain in Dakar), I found a photo that I mention in my film, a photo showing a man presenting a plant and the caption - "Textile plant likely to replace hemp" - indicating that these were textile plants likely to replace existing plantations. In this photo, I immediately saw the colonial interest in this plant, which is only mentioned in terms of how it could be exploited. The aim of this first project was to bring these elements together in order to reconstruct the links and issues involved in the botanical missions, and hence their history, which spans more than two centuries.

Nicolas Pirus will present his next film at Le Fresnoy in September, as part of the study program (Vera Molnár class 2023-2025)